Love’s Two Languages: Bread and Basin | Daily Readings | Holy Thursday | April 17, 2025

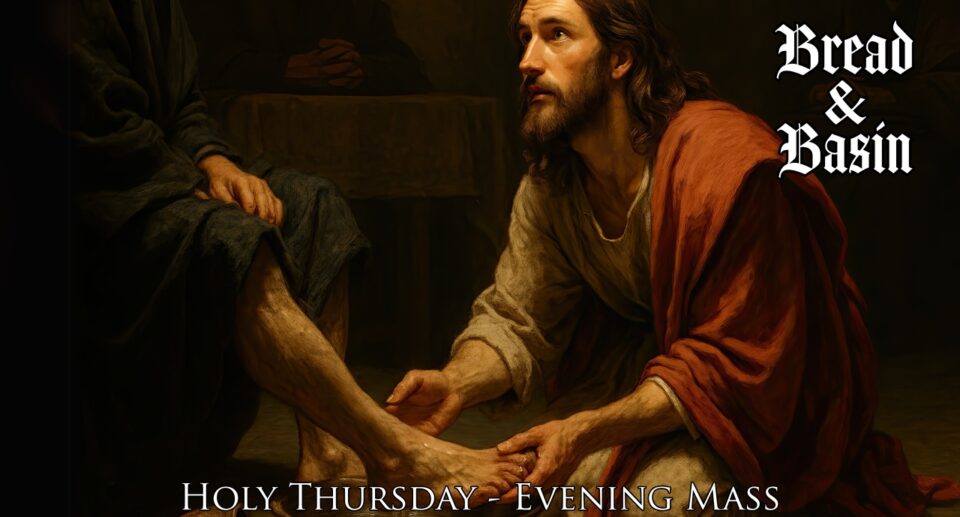

Tonight we witness two profound expressions of the same divine love: Christ who kneels to wash feet and Christ who gives himself as food. Neither gesture is complete without the other.

Through this reflection, you’ll discover:

- How the Passover context illuminates Christ’s gift of the Eucharist as his true Body and Blood

- Why foot-washing was so shocking in first-century Palestine and what it reveals about authentic love

- The essential connection between receiving Christ in Communion and becoming Christ for others

- How these twin mysteries call us to both worship and service in our own lives

Readings covered: Exodus 12:1-8, 11-14; Psalm 116:12-13, 15-18; 1 Corinthians 11:23-26; John 13:1-15

Perfect for deepening your Holy Thursday experience as we enter the Sacred Triduum.

#HolyThursday #LordsSupper #RealPresence #FootWashing #ServantLeadership #SacredTriduum #CatholicFaith

Love’s Two Languages: Bread and Basin

Water splashed over dusty feet. The sound punctuated the stunned silence that had fallen over the upper room. The Master—on his knees, a towel wrapped around his waist—moved from disciple to disciple, performing a slave’s task with a king’s dignity.

“You will never wash my feet,” Peter protested.

Jesus looked up at him. “Unless I wash you, you will have no inheritance with me.”

That same night, Jesus took bread, blessed it, broke it, and gave it to his friends with words that must have left them breathless: “This is my body, which will be given for you.”

Not “This represents my body.” Not “This reminds you of my body.” But “This IS my body.”

Tonight, as we enter the sacred Triduum, we witness two profound expressions of the same divine love: Christ who kneels to wash feet and Christ who gives himself as food. Neither gesture is complete without the other. Together they reveal the full meaning of what Jesus meant when John tells us, “Having loved his own who were in the world, he loved them to the end.”

Our first reading from Exodus sets the stage. It describes the original Passover—that night when Israel ate the unblemished lamb whose blood on their doorposts would spare them from death. God commanded them, “This day shall be a memorial feast for you, which all your generations shall celebrate.”

For centuries, Jewish families had faithfully reenacted this meal, not merely recalling a past event but becoming participants in the Exodus itself. When Jesus transformed this meal, he was establishing a new participation in divine reality. The blood of the lamb on wooden doorposts becomes the blood of Christ on the wooden cross. The flesh of the lamb that nourished Israel for their journey becomes Christ’s flesh that nourishes us for our journey to eternal life.

Our psalm response voices thanksgiving for this gift: “How shall I make a return to the LORD for all the good he has done for me? The cup of salvation I will take up, and I will call upon the name of the LORD.” The “cup of salvation” has been transformed. No longer just ritual wine commemorating ancient deliverance, it has become the very blood of Christ—the definitive salvation cup we are privileged to share.

Paul’s account of the Last Supper in our second reading emphasizes Christ’s clear declaration: “This is my body” and “This cup is the new covenant in my blood.” These aren’t mere symbols but reality. As Jesus taught in John 6, “My flesh is true food, and my blood is true drink. Whoever eats my flesh and drinks my blood remains in me and I in him.” When many disciples found this teaching too difficult and abandoned him, Jesus didn’t call them back saying, “I was speaking metaphorically!” Instead, he let them leave, then asked the Twelve if they too would go.

The earliest Christians took Jesus at his word. Ignatius of Antioch, taught by the Apostle John himself, wrote in 107 AD that heretics “abstain from the Eucharist…because they do not confess that the Eucharist is the flesh of our Savior Jesus Christ.” Justin Martyr explained in 151 AD that the Eucharistic food “is both the flesh and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh.”

Yet John’s Gospel, rather than describing the bread and wine becoming Body and Blood, focuses entirely on Jesus washing his disciples’ feet. Why this difference? Not to deny the Eucharist’s reality, but to reveal its deepest implications. The Eucharist is not just something we receive but something we become. Christ gives himself as food so that we might be transformed into him—into living embodiments of self-giving love.

When Peter resists this humble service, Jesus insists: “Unless I wash you, you will have no inheritance with me.” He’s saying, in effect, unless you allow me to love you with this radical, boundary-crossing, status-reversing love, you cannot share in what I’ve come to bring.

The foot-washing was particularly shocking in first-century Palestine. This task was considered so degrading that Jewish servants were typically exempt from it—it was assigned to Gentile slaves or performed by wives for husbands, children for parents. For a teacher to wash his disciples’ feet inverted every social hierarchy they knew.

After completing this act, Jesus explains: “Do you realize what I have done for you?… I have given you a model to follow, so that as I have done for you, you should also do.” The model is not just external action but the interior disposition that motivates it—love that holds nothing back, love willing to assume the lowest position, love that serves without calculating cost or return.

This connection between receiving the Eucharist and becoming Eucharistic people is powerfully confirmed by Paul’s linkage of the Lord’s Supper with concern for the poor in 1 Corinthians. He rebukes the Corinthians for celebrating the Eucharist while ignoring the hungry in their midst: “When you come together, it is not the Lord’s supper that you eat…” Their failure to recognize Christ in the needy contradicted their claim to recognize him in the sacrament.

In an age of deepening division, the foot-washing reminds us that authentic love bridges every social barrier. In a culture that increasingly reduces human worth to productivity and achievement, Jesus demonstrates that true greatness lies in service. In a world where hunger—both physical and spiritual—remains pandemic, Jesus provides the definitive solution: himself, given completely for our nourishment and salvation.

The Eucharist without service becomes sterile ritualism. Service without the Eucharist becomes mere humanitarianism without supernatural power. Together, they form the complete revelation of divine love—vertical and horizontal, receiving and giving, worship and witness.

Tonight’s liturgy invites us not just to commemorate these events but to participate in them. After Communion, the Blessed Sacrament processes to an altar of repose, where many will keep vigil—recalling Jesus’ words in Gethsemane, “Could you not watch one hour with me?” This vigil connects tonight’s celebration to tomorrow’s commemoration of the Passion, where the body given and blood shed at the Last Supper is offered on the cross.

The word “Eucharist” comes from the Greek for “thanksgiving.” Tonight, we give thanks not just with words but with our whole selves. We give thanks for the God who becomes bread to nourish us and for the God who kneels to wash us. We give thanks for the astonishing truth that the Creator of the universe so loves us that he gives himself completely—as food for our journey and as model for our lives.

As we enter these most sacred days, may we open ourselves to this love in both its forms—the love that feeds and the love that serves. May we receive with profound gratitude the gift of Christ’s true presence in the Eucharist. And may we allow this gift to transform us into people who, like him, are willing to be broken and poured out for others.