The Perfume & the Plot: Extravagant Love Meets Deadly Calculation | Daily Readings | April 14, 2025

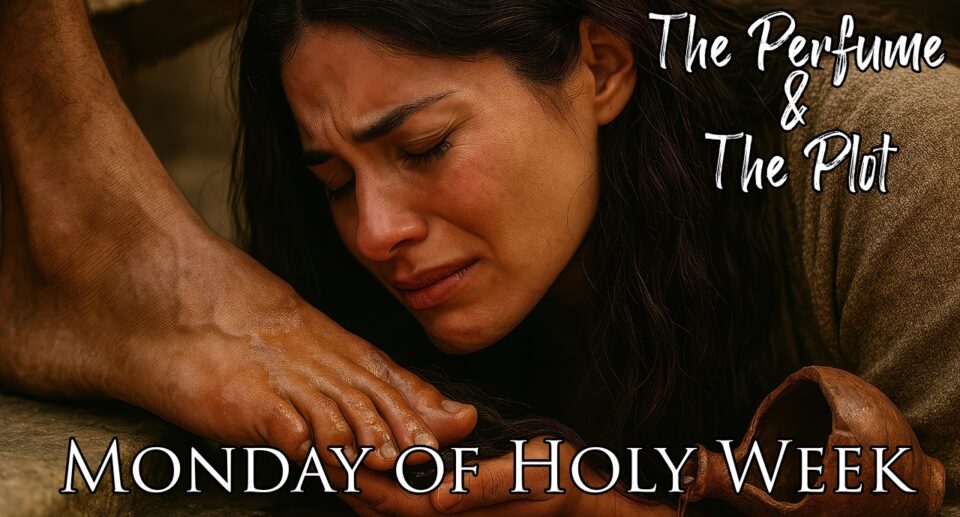

When Mary broke open a jar of expensive perfume worth a year’s wages to anoint Jesus’ feet, she ignited both admiration and outrage. Today’s Holy Week reflection explores this pivotal moment when extravagant devotion collided with calculating betrayal.

Through this reflection, you’ll discover:

- Why Mary’s seemingly wasteful act reveals the true nature of discipleship

- How Isaiah’s Servant Song illuminates Christ’s mission of gentle justice

- The connection between Mary’s broken alabaster jar and Christ’s coming sacrifice

- Why resurrection life threatens death-dealing powers then and now

Readings covered: Isaiah 42:1-7; Psalm 27:1-3, 13-14; John 12:1-11

Perfect for anyone seeking to deepen their Holy Week journey, struggling with what wholehearted devotion looks like, or facing opposition for their faith.

#HolyWeek #HolyMonday #MaryOfBethany #ServantSong #ExtravagantLove #Anointing #JesusInBethany

The Perfume and the Plot

The smell hit them first.

It wasn’t the usual aroma of a dinner party—bread baking, meat roasting, wine being poured. This was something else entirely. Exotic. Powerful. Excessive.

Before anyone could identify the source, they saw Mary. On her knees. Hair loose and flowing—scandalously so. Doing something so unexpected that conversation died mid-sentence.

She had broken open an alabaster jar of pure nard. A year’s wages now dripped between her fingers, soaked into her hair, pooled around Jesus’ feet. The oil glistened in the lamplight as she spread it with her unbound hair.

No one moved.

Then Judas, always calculating, found his voice: “Why wasn’t this perfume sold and the money given to the poor?”

His words hung in the air alongside the heavy scent, both filling the room with a strange tension.

Six days before Passover. Jesus has come to Bethany, where something unprecedented has already happened—a man four days dead now sits at the table eating dinner. Lazarus, restored to life, breaking bread with the one who called him from the tomb.

Here in this scene, the gospel writer reveals three distinct responses to Jesus that we still see today: extravagant devotion, calculating criticism, and murderous rejection.

Mary’s response is pure abandonment—financially, physically, socially. She holds nothing back. The cost of the perfume was astronomical—three hundred denarii, a year’s wages for a laborer. In today’s terms, perhaps $30,000 or more of pure luxury, poured out in seconds.

Beyond the financial recklessness, there was the social impropriety. In that culture, respectable women didn’t let down their hair in public. This was an intimate gesture, done before the eyes of men who were not her husband. Yet she uses those tresses to wipe his feet, combining extravagance with profound humility.

What drove her to such an act? John doesn’t tell us explicitly, but context provides clues. This is the same Mary who sat at Jesus’ feet to learn while her sister bustled about. The same family who had just experienced Lazarus’ resurrection. Her gesture speaks of gratitude beyond words, recognition beyond conventional expression.

Then there’s Judas, whose response seems reasonable on the surface. Shouldn’t such wealth be used for the poor rather than literal evaporation into the air? But John reveals the corrupt heart behind the righteous words: “He said this not because he cared about the poor, but because he was a thief; he kept the common purse and used to steal what was put into it.”

Here is calculation disguised as compassion, self-interest masked as social concern. It’s a response that quantifies everything, reduces the sacred to the transactional, sees only what can be measured and managed.

Finally, the chief priests plot murder—not just of Jesus, but of Lazarus too. Why? Because “on account of him many of the Jews were deserting and were believing in Jesus.” Evidence of resurrection was drawing too many people away from their authority. Their response to divine life-giving power is elimination of the evidence.

These three responses—devotion, calculation, and rejection—stand in stark contrast. But they don’t appear in isolation. They interact, comment on each other, reveal each other’s nature.

When Mary pours out the perfume, it’s Judas who objects. When Judas frames his greed as concern for the poor, it’s Jesus who defends Mary’s gesture. When the crowd comes to see both Jesus and Lazarus, it’s the chief priests who plot to kill them both.

This interplay invites us to consider our own response to Jesus this Holy Week. Are we most like Mary, Judas, or the chief priests? Or do we oscillate between these postures, sometimes pouring out love without reservation, sometimes calculating what discipleship will cost us, sometimes even rejecting evidence of resurrection that would require us to change?

Today’s readings provide a framework for understanding these responses more deeply.

Isaiah’s servant song describes one who “will not cry or lift up his voice, or make it heard in the street; a bruised reed he will not break, and a dimly burning wick he will not quench.” This is leadership exercised not through dominating power but gentle persistence. The servant establishes justice without crushing the vulnerable. He liberates by becoming “a light for the nations, to open the eyes that are blind, to bring out the prisoners from the dungeon.”

This portrait of the servant-messiah stands in stark contrast to what many expected of a liberating king. It’s a mission that confused even Jesus’ closest followers and infuriated the religious authorities. It’s a mission that still challenges our understanding of how God works in the world.

Against this backdrop, Mary’s apparent waste makes profound sense. She recognizes in Jesus this servant who brings true justice through self-giving love rather than dominating power. Her response is not measured calculation but overwhelming gratitude. She intuitively understands what even the disciples haven’t yet grasped—that the pathway of this Messiah leads through death to resurrection. Her anointing is preparation for burial, a prophetic act recognizing the sacrifice to come.

The psalm adds another dimension: “The LORD is my light and my salvation; whom shall I fear? The LORD is the stronghold of my life; of whom shall I be afraid?” This confidence allows the psalmist to face threatening armies without fear, to seek God’s face even when human faces turn away in rejection.

This fearlessness characterizes Mary’s action. She risks criticism, risks her reputation, risks financial security—because perfect love casts out fear. By contrast, both Judas and the chief priests act from fear—fear of not having enough, fear of losing authority, fear of Roman reprisal. Their calculations and plots grow from insecurity rather than confidence in God’s saving power.

As we journey further into Holy Week, these readings challenge us to examine what shapes our own response to Jesus.

What would it look like for us to respond like Mary? Not just incremental devotion, adding a little more religious observance to our lives, but whole-life abandonment to Christ. Not calculating the minimum required, but pouring out our best without reservation. Not caring what others think, but focused entirely on honoring Jesus.

Mary’s extravagance prefigures Christ’s even greater extravagance on the cross. Her broken alabaster jar foreshadows his broken body. Her costly perfume anticipates his priceless blood. She pours out her treasure; he will pour out his very life.

Yet alongside Mary’s devotion, we must honestly acknowledge the Judas-tendency in ourselves—the part that calculates, preserves, holds back. The part that uses spiritual language to mask self-interest. The part that keeps the ledger of what we’ve given and what we’ve received.

And if we’re brutally honest, we might even recognize the chief-priest-tendency—our resistance to evidence that would require us to change, our preference for eliminating threats to our authority rather than encountering the God who raises the dead.

The fragrance that filled that house in Bethany reaches across time to us today. It carries the aroma of abandonment—not abandonment by God, but abandonment to God. It invites us to break open our alabaster jars—the carefully protected vessels of our hearts, our possessions, our reputations, our very lives—and pour them out in recognition of who Jesus is and what he has done.

For some of us, that might mean financial generosity beyond what seems reasonable. For others, it might mean social risk—standing with Christ when it costs us status or relationships. For still others, it might mean breaking open hardened hearts to let love flow freely again.

Six days before Passover, Mary anointed Jesus for his burial. But her act of devotion did something else too. It created a sensory reminder of love’s extravagance that would linger in that room, cling to Jesus’ skin, and perhaps even follow him through the days ahead—through his entry into Jerusalem, his last supper with disciples, his betrayal, trial, and crucifixion.

The text doesn’t tell us, but one wonders: Did those gathered beneath the cross catch a faint note of that perfume mingled with the scent of blood? Did it carry a whisper of devoted love amid history’s greatest act of salvation?

This Holy Monday, as the sacred journey toward the cross continues, may we find ourselves less with Judas in calculation, less with the chief priests in rejection, and more with Mary—on our knees, inhibitions abandoned, pouring out all we have in recognition of all Christ is.